|

|

|

|

|

|

Few indeed are the western readers who have never encountered a book by Peter Watts. For more than a quarter of a century, he produced popular, authoritative and hugely entertaining western novels as "Matt Chisholm", "Cy James" and "Luke Jones". Born in London on 19th December 1919, Peter went on to become a Civil Servant and founder of the Electro Acupuncture Voluntary Society of Britain and Ireland. His writings also appeared under the names "Duncan Mackinlock" and "Tom Owen", but no matter what the name, it was the uniquely readable style he employed to tell his stories that earned him world-wide respect as a master of his craft. In the late 1970s, I was fortunate enough to meet and become friends with Peter. In 1980 I conducted the following interview with him. It has never appeared in this format anywhere else. When he died on 30th November 1983, the genre lost not only one of its most accomplished exponents, but also a warm and witty human being.

DW: Could you tell us a little about your early life and how you got interested in westerns?

PW: I was trained as an artist and given an art school scholarship. Writing interested me from the age of about fourteen, and I never saw myself as being anything but a writer. Strangely enough, I have long been a professional writer and an amateur artist. In my late teens, I knocked about as a factory worker and such-like, did a little commercial art and then went to war like most other people of my age. That meant the Western Desert and the Burma border. All good stuff for a writer. I wrote steadily through the war, but had all my notes pilfered before I could bring them home. What thieves could do with a hundred thousand words of bad writing I'll never know. Maybe they had a literary turn of mind, and turned them into bestsellers! Since the war, I have been a civil servant, as which I initiated an edited two official magazines -- which was surprisingly interesting and I loved it. My first novel, Out of Yesterday, was published about 1950. Getting the second one into print seemed to be almost impossible. Many writers have experienced the same difficulty with their second book. I was just not good enough. A veteran writer looked at my work and told me that what I was producing could not be called writing at all. He told me in no uncertain terms the difference between what I was doing and real writing. In short, I knew nothing about the craft whatever. He was right, and today I still see work -- much of it published -- which is the produce of people who don't know what writing is. I swore I would never write again. I did, of course, but did not get another book in print for another ten years and about ten books later. This was a western called Halfbreed, which was bought outright for fifty pounds by Panther Books. It was a marvelous feeling.

DW: To what system do you write? Is it a nine-to-five thing or part-time?

PW: I'm not aware of writing to any system, though possibly I do. The method I use for writing westerns of a popular kind is to type the story in final form straight onto the typewriter. On the whole, I correct but don't rewrite to any extent. Maybe a page or two gets done again. If fine writing is demanded -- say, a straight passage in a straight novel, an essay or a poem -- that's usually started by hand and continued on the typewriter once I have the style and pace decided. This kind of work is usually started at about eleven at night till two in the morning. Writing generally is carried out intermittently throughout the day from seven in the morning until the early hours of the following morning, usually seven days a week. Normally, I dislike going through the day without writing. In the old days, when I was doing a regular job during the day, I worked at night and at weekends.

DW: Doesn't that sort of routine tend to kill family life?

PW: Only if you let it. I never cut myself off. People come and go in my workroom all the time. Writing is the loneliest job in the world, and though a writer needs to be capable of complete concentration, he also needs to see people. People prevent him from getting stale and withdrawn. They continually trigger ideas and stimulate his mind. That's what he needs -- not inspiration, but stimulation.

DW: How long does it take you to complete a manuscript?

PW: Impossible to say. When an idea comes, I usually put it down as the opening chapter or chapters of a book. That might be shelved for a year or two. In the old days, when I only had the evenings to work in, a western would take ten days to two weeks. Now I never hurry, and take my time, doing other jobs between chapters. I don't like to be hurried. In the days when I had to hurry, I did one book in five days -- the novelisation of a film. Having a deadline that panics you is no bad thing. There are times when you work much better under pressure. I suppose I give myself a month of working time for a short book these days.

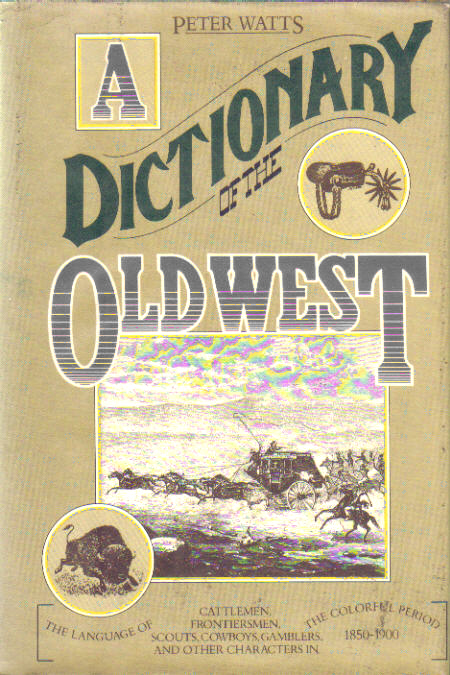

DW: Tell us a little about your nonfiction work, and in particular your Dictionary of the Old West.

PW: There have been a number of books written under other names besides Matt Chisholm and Cy James, some so hastily-written that I like to disown them. There have been one or two war books, a couple of straight novels, some novelisations of film scripts and a good many short stories. The shorts have been mostly published abroad. There is almost no market in this country for light short stories. Publishers believe, and probably rightly, that the British don't like the short story. Personally, I love to both read and write them. The Dictionary was a labour of love, as they say. My publisher in New York showed enormous care in its production, and came back to me time and again in the pursuit of accuracy. Their thoroughness was a revelation, and they taught me a great deal about conscientious publishing. They used a number of my own drawings. Probably the most useful thing the Dictionary did for me was to provide me with some very good correspondents who are also interested in the actual language of the West. They have all been wonderfully helpful, and there is now a whole volume of editions to the Dictionary. One day, say in ten years' time, I hope to do an amended version.

DW: Quite obviously, the West has facinated you over a number of years. Can you explain why it facinates not only you, but so many people all over the world?

PW: It must have started with me when my father read Zane Grey's The Rainbow Trail out loud to me. I followed it up by reading Wildfire, which I thought to be pretty dangerous stuff, and wildly sexy. Then I saw Richard Dix in Cimarron, the movie, and thought it was wonderful. Later, when I started to be a serious writer at the age of about twenty-six, I used to read westerns for relaxation. I was studying the American Indians at the time. It seemed natural for me to try my hand at westerns. It was then that I started to make my own list of words used in westerns, because I did not know of any sure guide to them. Without knowing it, I had started what, twenty years later, would be my Dictionary of the Old West, 1850-1900.

But that's not really the answer to your question. The west continues to fascinate the world on two quite different levels. One is the legend -- on which most works of fiction are based, and which bear as much resemblance to the reality as Robin Hood or Dick Turpin did to the original. The only likeness that I can see is that the characters wore guns and rode horses. The second level is the reality of the west. The legend is too big and ubiquitous to be ignored. You could almost say that it is of more importance than the reality. The reality, of course, was even more wonderful, much sadder and impressive. The basic and original facts are, of course, shared by both levels. They are a) a technical culture meeting a stone-age culture head on -- the last time such a thing on such a scale would be witnessed by mankind. It was also the only time such a thing could be recorded in writing. And b) In many places, men were forced to create and maintain their own justice. In some cases, a man carried his own justice on his hip. There was no other.

You can hardly blame nine-to-five humanity for seeing the drama of it all. Why, it was the source of pulp literature even while it existed. Many of the legendary heroes were created heroes in their own right while they lived. Otherwise many of them would never have been heroes at all. Let's mention no names! It spoils the fun.

DW: So how do you approach the creation of a character like Rem McAllister or Joe Blade?

PW: I don't think any writer could truthfully tell you how he goes about creating a character. It is a rare accomplishment, and few writers of popular fiction have it. Many publishers are content with two-dimensional characters in westerns because they know no better and imagine their readers don't know any better, either. They're quite wrong, of course, because there is no typical western reader. I have met and corresponded with quite a number, among whom have been a factory worker in Glasgow, an accountant in Monaco, a professor who speaks eight languages, an old retired lady in Cornwall, a schoolgirl in Kansas, a senior civil servant in Cheltenham and a pensioner in Oregon. In Britain, where there is a great deal of literary snobbery, you will find many hidden readers who will never admit to their vice. On London tubes, the usual subterfuge is to read them hidden in a newspaper.

DW: That being so, do you think that poor characterisation affects the sale of westerns in the U.K.? Does snobbery come into it?

PW: I'm quite sure it does. I learned when I was a publisher's reader that, on the whole, you can only hope to sell a certain type of western in this country, or, to put it another way, you must package it not as a western, or as a western in the lighter popular category, at a low price and aimed at a reader who reads only light western fiction -- the avergage western reader as imagined by publishers. In the States, that is not the case. There, a writer may be a novelist who writes stories based on the west, as opposed to a "western writer", and be accepted as a respectable creative artist. There have been a number of books in the genre which have proved themselves as respectable novels and showed a talent bordering on genius -- one of them was Little Big Man. One or two Britons have produced impressive and serious novels set in the west -- an example being John Prebble with his The Buffalo Soldiers.

To return to character -- the public are never as gullible as some writers think they are. They quickly tire of flat characters who don't possess interesting human qualities and the writer who is content to write about such characters will find that his readership will decline.

DW: In your opinion, what then are the necessary ingredients of a western hero?

PW: It's essential that the central character of a story should be a hero -- not a principal character. He should have heroic proportions. He needn't, indeed, he should not show characteristics which his creator and possibly his readers could despise or find abhorrent. There are exceptions to every rule, but that is a good general rule. The creation of McAllister came about when my editor at Panther Books, an experienced man and a first-rate editor, asked me to create a series. That was when series were only just being launched. I took a name from a book I had written several years before, and made the character into a fellow who maybe chased the girls and drank too much at times. He could not be an old-fashioned, purely noble kind of hero -- he would have bored the modern reader. I decided I didn't want him mean, petty, cruel or in any way despicable. In other words, if a young reader came to identify with him, he would be identifying with something worthwhile. McAllister may have been the kind of man who could say, "Ma'am, I never struck a woman -- unless she deserved it," but he would never break his word or let a friend down. He would fight at the drop of a hat, but he never bullied anybody in his life.

McAllister has appeared in over thirty books, starting in 1963 with The Hard Men and ending up in 1974 with The McAllister Legend. He's like an old friend -- he must be, he's earned me my living! I don't have to think about what he would do or say in given circumstances -- he decided that long ago. Once you have created a firm character, your stories will grow naturally out of him. So character solves the problem of plot. All the subsidiary characters should take their cue from the hero and should be drawn with the same care, so that the hero exists in a world of real, three-dimensional people.

DW: Broadly speaking, what makes a western a western, and what do you think are the essential ingredients of a successful western story?

PW: It's a western generally when it's a story set between about 1850 to about 1890. Its venue can be anywhere in the western states, from Arizona to Washington State, including Oklahoma and Texas, but with California's west coast slightly questionable. It can be set among Indians, cattlemen, thieves, gold-seekers, lawmen, outlaws -- it doesn't matter who. I think it goes without saying that the story should have a few hairs on its chest. The plot should be simple. The hero must be up against odds and physical danger. The vital ingredient is style. The western is one form of popular art that does not need originality of plot, though that can help. It insists on style. The reader must hear the storyteller's voice. He or she must feel that the story comes straight from the horse's mouth, as it were. Here lies the weakness of so many contemporary western writers -- they lack style. They also lack a feel for character. The moment the reader feels that he or she is following the fate of a real flesh-and-blood character, the plot can do what it likes. The reader must care about what happens to the hero. The last essential, sadly lacking in many westerns, is correct background facts. There's always some smart alec in the audience who will jump on an error of fact and let you know about it. The readership is thick with experts, some of them more misinformed than the writers.

DW: What great western writers have you admired?

PW: As I told you, I started on Zane Grey. I find him dull to read now. The men I learned most from were Frank O'Rourke, Norman Fox, Luke Short, Ernest Haycox, Alan Le May, Will Henry/Clay Fisher, Jack Schaefer, Steve Frazee, Howard Rigsby, Les Savage Jr, of, and a dozen more. The giants of the last generation of western writers started in the pulp magazines which don't exist now. What this generation of writers needs is a market for short stories. I love 'em -- they're the greatest fun to write. It was the pulps that gave the writers I've mentioned the experience and confidence they needed. They learned to create characters and knock off a story at the drop of a hat. Like a musician or an athlete, a writer has to keep in practise. Seeing himself in print gives him confidence and shows him better than any hand-written or typed page, the visual weight of what he's written.

DW: What good western writers in your opinion do we have today?

As many as ever, but they're not getting the opportunities the last generation had. There are plenty in the Western Writers of America. If I mention some, there are probably many others I should name, but there come readily to mind such writers as Elmer Kelton, Louis L'Amour, Dorothy Johnson, Carter Travis Young, Dudley Dean, Budd Arthur, Bill Gulick, Ray Hogan -- and plenty more. There are the Overholsers, D B Newton, Lewis B Patten, Thomas Thompson, Steven C Lawrence, George R Stewart, Michael Straight, many find writers. I'm not sure they're all still alive, but they should be.

DW: What would you like to do in the future?

What I'm doing now, only better. There's no end to being a writer, and unless prevented by physical incapacity, you can write till you die. My immediate future is filled with a popular western series, Blade. I have two series novels on the stocks -- one set in the west, the other covering the Vikings, which I have been preparing on and off over the last couple of years. I would very much like to produce a fully-illustrated book covering the appearance of the west right through the nineteenth century -- costumes, equipment, guns etc., An immense task, but I would like to have it as a twin to my Dictionary.

DW: Any chance of your doing any stories about McAllister again?

PW: We're talking at the moment of doing a new series of about a half-dozen again. I look forward to having a lot of fun with him.

DW: So what's the future for the western?

PW: It'll most likely survive. About ever six or seven years we hear that sales are slumping. But they have always picked up again. On the whole, westerns do not have runaway success, but they still earn bread-and-butter for a writer. And of course, there's jam on the bread if one is made into a film.

DW: Talking is thirsty work. How about another drink?

PW: An inspired thought. You pour.

|